Communication: What scientists 'know'

"A new scientific study shows..."

Whether we get our news on tv, social media, or the internet, this is a common headline. And all too often, what scientists have 'found' is something that seems to conflict with another scientific discovery from the past. Wondering what’s up with this? Are scientists lying to us? Are they just confused? Usually not. It just has to do with how we do science.

Imagine you asked me what the weather was like and I said it’s 60 degrees out. You then walk outside and find that it’s 60 degrees and raining. I wasn’t wrong and I wasn’t lying to you, I just didn’t have all of the information.

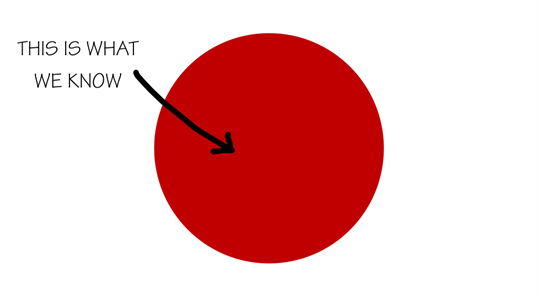

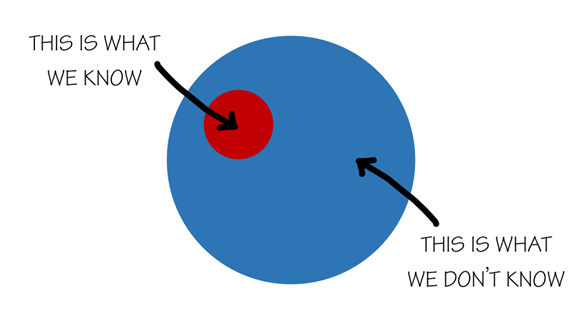

Science is similar. When scientists publish a paper, they are saying “this is what we know.” They have posed a question, gathered some data, and drawn the best conclusions they can from those data.

What is not always clearly stated, but needs to be recognized, is that there is also a “this is what we don’t know.” That can be assumed to be everything else.

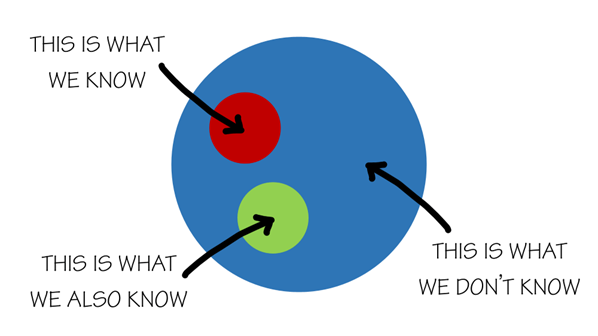

So, when two “scientific studies” arrive at conclusions that clash with each other, it doesn’t always mean that someone is wrong. It could just mean that different groups of researchers have gathered different sets of knowledge within the bigger reality.

Let's look at a practical example. I'm a runner, so I have a great interest in all of the lore around whether running is good for your knees or bad for your knees. To really answer that question, the scientific space that needs to be explored is vast. How does someone's age impact the effect? What if they also do strength training? If there is a negative effect, how many miles is too many? What about road running versus trail running?

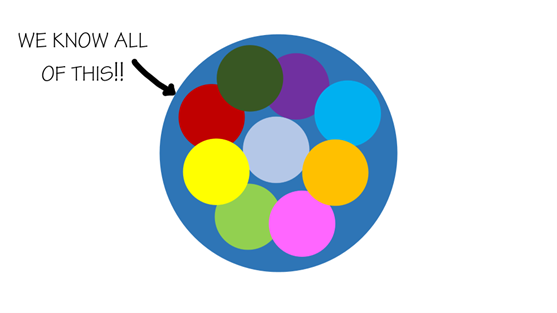

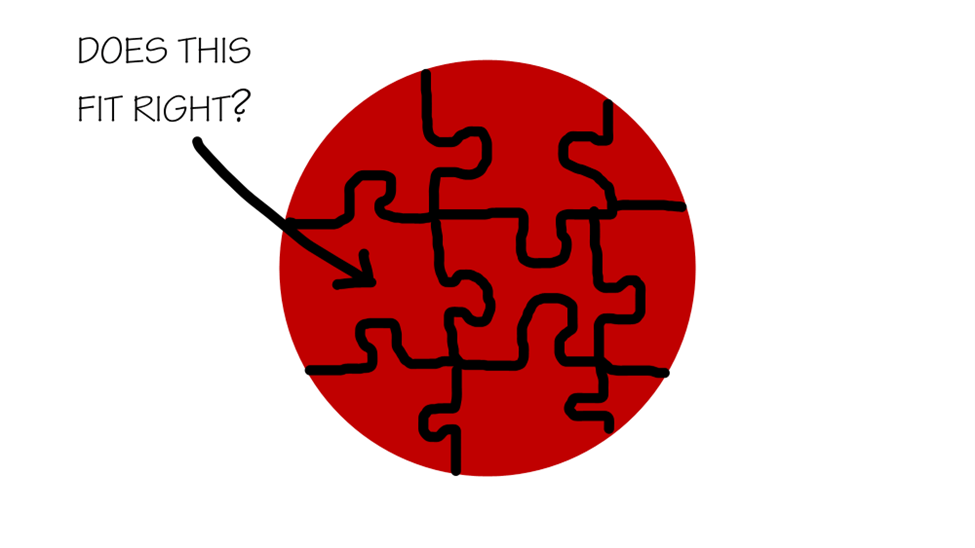

All of these are different pieces of that big circle, and covering the entire circle is so much work that no single study can accomplish it. So, instead, each study seeks to add something, and as we keep doing this, the fuller picture will start to emerge.

It’s also important to know how scientists put together each circle of knowledge. As I mentioned above, we design experiments, collect data, and then analyze the data to draw the best conclusions we can.

It’s like trying to put together a puzzle, but without having the picture on the box to guide you. As we gather data, we’re trying to put pieces together and see if hey fit. Sometimes it seems we have a match, but we later realize that there’s a piece that fits better.

In these cases, we have to step back, take a new look at all of the data, and possibly revise our conclusions. While it may seem like science is a well-ordered process, in reality it’s complicated, messy, and always changing.

The take home from all of this is that when you hear that a “study has shown…”there is a good chance that it is accurate, but as scientifically engaged citizens, we also need to think about what the study didn’t show and what we still need to learn.

For more leadership ideas, check out Labwork to Leadership